The OODA loop

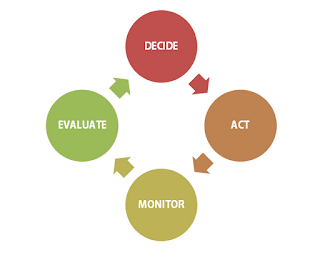

Decision making is at the heart of management and leadership. Typically it is a process about closing the gap between where we are and where we want to be. The process can be simplified as follows: Once we decide, we act. After acting, we monitor the results of our actions. Finally, we evaluate the results we’ve monitored. This can be presented as a Decision Execution Cycle (DEC) shown below:

|

| Decision Execution Cycle |

There is nothing complicated about this. The DEC is a common sense approach that few would argue against and many of us will recognise this as being valid for most organisations. Its simplicity is central to its success, but to throw a different light on this I want to introduce the concept of a similar but subtly different model for understanding decision making in action – the wonderfully titled "OODA loop".

The OODA Loop

One of the most interesting and fascinatingly simple models in the study of how people actually make decisions in complex environments is a theory called the OODA Loop. The loop originated from Colonel John Boyd of the US Air Force who originally proposed the loop as a way of explaining how fighter pilots in the Korean War were able to outperform their communist opponents with such apparent ease and regularity. The consequent theory became hugely popular and remains one of the cornerstones of military doctrine. The loop also has application to the business world, as we shall see.

|

| The OODA Loop |

The loop as described by Boyd involves four actions, Observe, Orient, Decide and Act, occurring in a sequenced process. When completed more rapidly than the opponent, completing the loop allows the pilot the opportunity of seizing the initiative in the complex and challenging environment of a critical incident or swirling dogfight. The principle of the loop from a military perspective is that the faster a decision maker can make his way around the loop, the more likely he is to stay one step ahead of his enemy.

The Observe phase is about awareness. It is the unfolding situational data reaching the pilot (or manager in a business sense). This awareness is aquired through sensual and technical means and relates to both the external world outside of the individual and the internal world of what is going on within the person making the decision (yes, feelings are data - you know this to be true).

Orient, the next factor, becomes the basis for decision and action. It is here that we assimilate the data that is collected in the observe phase. Thus it is not simply what we see but how our training, background and life experiences allow us to create a contextualised story about what is going on. As Boyd described it:

“Without our genetic heritage, cultural traditions, and previous experiences, we do not possess an implicit repertoire of psychological skills shaped by environments and changes that have been previously experienced”.

Thus orient becomes the lens through which we view the situation. This is where we bring ourselves, and all our history, knowledge and bias (conscious or otherwise) to the situation. It includes our values and beliefs, and the application of our own intuition. This makes our decision making very personal.

These internal models and paradigms are forever being recreated, analysed and assessed. It might be argued then that there exists a sub-loop within the main loop where our own orientation is being constantly reappraised through an internal process of reflection and reappraisal. As the person works their way around the loop they reassess their situation against these eternally developing paradigms and schemas that are influential in guiding the formation of a hypothesis and thus guiding them towards making a decision.

As the US Marines have it:

These internal models and paradigms are forever being recreated, analysed and assessed. It might be argued then that there exists a sub-loop within the main loop where our own orientation is being constantly reappraised through an internal process of reflection and reappraisal. As the person works their way around the loop they reassess their situation against these eternally developing paradigms and schemas that are influential in guiding the formation of a hypothesis and thus guiding them towards making a decision.

As the US Marines have it:

“We should base our decisions on awareness rather than on mechanical habit. That is, we act on a keen appreciation for the essential factors that make each situation unique instead of from conditioned response… since all decisions must be made in the face of uncertainty and since every situation is unique, there is no perfect solution to any battlefield problem. Therefore, we should not agonize over one. The essence of the problem is to select a promising course of action with an acceptable degree of risk and to do it more quickly than our foe. In this respect, “a good plan violently executed now is better than a perfect plan executed next week”

Warfighting - US Marine Doctrine (1997)

This suggestion of hypothesis generation as a key part of decision making is supported by Gary Klein’s work. Klein, a widely published and much respected voice in the field of naturalistic decision making argues that experts have highly tuned senses of intuition formed by extensive experience. This, Klein argues, enables them to spot patterns and identify the early onset of certain situations, or to spot the errors in apparently novel solutions. This makes them very powerful individuals - on the battlefield or in the boardroom.

Within the orientation phase of the loop, experts then are more able to apply some form of pattern match that allows them to select a ‘best outcome’ hypothesis in the decide phase of the loop.

Where this process of pattern matching turns up a blank, then a knowledge gap exists. Becuse of what we have discussed so far, it is fair to assume that inexperienced people are more likely to have a knowledge gap than experts. A subsequent decision then may not have such clear outcomes, but the data generated by observing the outcomes arising from the actions will be analysed and form part of the subsequent orient phase. Thus where there is a mismatch between intended and subsequent outcome, the expert is more able both to observe and orient the new data, coming potentially to a better solution more rapidly than the novice.

Decisions then are the manifestation of the early two factors, which Boyd also refered to as the finalised hypothesis. This is where the manager really has an opportunity to influence the outcome, using the data and understandings of it that have been gathered in the first two stages to decide upon a course of action.

The final stage is the action stage, where the decisions are put into effect. In well-oiled organisations the time taken between decision and action will be low. Inertia at this stage, especially in rapidly changing situations, can have a seriously detrimental effect, paralysing the organisation and creating more problems than solutions.

The loop as a creator of knowledge

The creation of new hypothesis from data allows the creating of new actions. The observations from these new outcomes generate new data forming part of the subsequent orient phase. Thus the loop is not only about learning and decision making, but it is also about the generation of new knowledge. It is about creating and shaping the world around us.

For organisations then, anything that encourages this type of learning and knowledge creation can only serve to help strengthen capabilities and expertise and , ultimately, mean that organisation is more aware and, potentially, more capable to cope with changing or new situations. Business wargames, red team events, simulations and decision making exercises all serve this purpose – they can turn uncertain situations into familiar territory and generate an adaptable, resilient organisations that is both well placed to take advantage of opportunities as they arise and be more protected against the potential problems and pitfalls that may threaten the current or future operation. For individuals of course the same is true, only more so and with the added benefits of enhanced self-awareness that can come with a deeper analysis and reflection of the experience of such events.

It is this level of expert capability that decision making exercises, red teams events and business wargames all seek to develop.

Using the loop to create competitive advantage

Quite simply the faster you can go round the loop the more able you will be to influence events. Boyd identified this as being essential in retaining the initiative in an aerial dogfight but the applications to business are obvious. The faster you can process the loop, the more opportunities there are for information acquisition and data processing through observation and orientation. These will lead into more opportunities for decision making and the creation of novel solutions and opportunities to drive the agenda.

But whilst your own capabilities might be great, it is the relative ability of your competitor to go through the same process that will have the most significant impact. If he is able to go round his loop faster than you are able to go around yours, then he is more able to claim the initiative, and create events to which you can only react. No matter how hard you try, he will always have the capacity to be ‘inside your loop’, better able to influence the outcome of the battle in his favour. In a nutshell, he is more likely to win.

“Without analysis and synthesis, across a variety of domains or across a variety of competing/independent channels of information, we cannot evolve new repertoires to deal with unfamiliar phenomena or unforeseen change” (Boyd)

So What?

So what’s the difference between the DEC and the OODA loops? The key elements of the deciding and acting – are consistent across the two models but Observe and Orient and different from Monitor and Evaluate. For me the difference between the two is all about competitive advantage. In the DEC the process is about completing the loop to generate a decision, whilst in OODA the emphasis is on gaining the initiative.

So I don’t think that the DEC and the OODA are telling us a different story, but rather that they place different emphasis on the same process. My own research confirms that decision making is an experiential process. As such what I experience may be different to what you experience. Who is right? The answer of course is not about who is right but about accepting that natural processes are at play that influence the outcome each of us will reach.

Linking to Intuition

Intuitive decisions are not guesswork. They are based on much deeper processes.

The military make a split. They suggest that intuition led decision making is most likely to be found closer to the front line, and that it will therefore be experienced most by more junior officers. They argue that further up the chain of command the process becomes more of an analytical and rational one where there may be a more obvious weighing up of the options. At the sharp end, where the conditions are more uncertain and the consequences more immediately telling, officers and NCO’s apply a different form of intuitive and naturalistic decision making. The loop, to some degree, can be applied at all levels.

One of the stated benefits of instruction for officers on military exercise and in training is to build his confidence in the commanders cognitive skills so that he is more likely to see a way to think through a problem rather than to ignore it, frame it or look to someone else to step in. This this way the commander is learning the importance of keeping the loop tight, unbroken and adaptive.

As the British Army puts it:

“Intuition is a recognitive quality, based on military judgement, which in turn rests on an informed understanding of the situation based on professional knowledge and experience”

The Germans have a much better word for intuition in this context: fingerspitzengefühl, which means, quite literally “fingertip feeling”. It represents that sense that the most able commanders have to appraise the situation (Observe and Orient in OODA terms). It is about harnessing that gut instinct of what is going on even if you can’t quite put your finger on exactly what that might be. Instead, you trust your feelings. The best commanders exhibit this tendency.

And so, I believe, do the best managers.

Comments

Post a Comment